In an effort to find out whether care has been affected, the director of Waterloo Region's Emergency Medical Services says he will review all calls over the last two months.

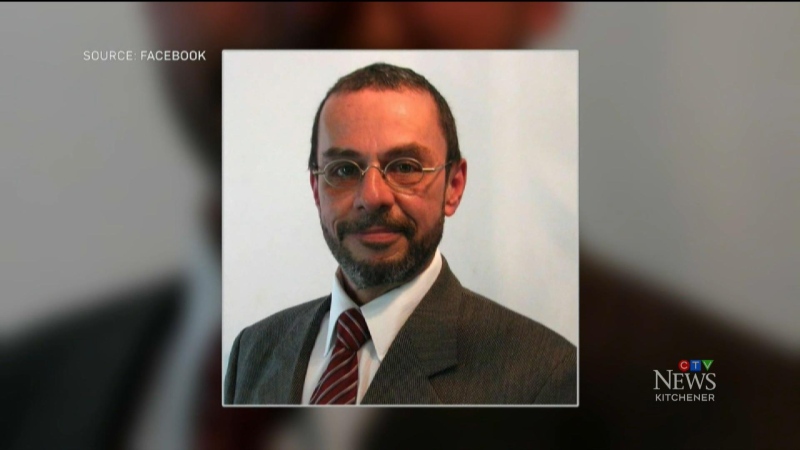

John Prno adds that he is committed to finding out if backed up emergency rooms played a role in changing the level of care that paramedics were able to provide.

He will be reviewing every ambulance call that came in during the first two months of 2011. That likely means thousands of calls to examine.

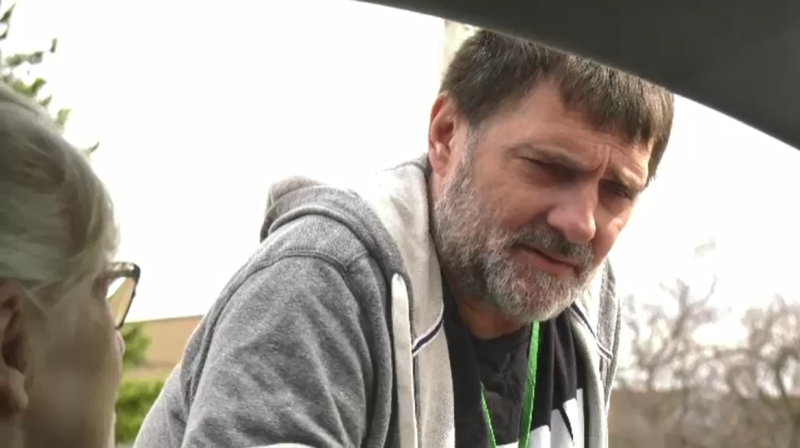

Paul Stack is an advanced care paramedic who has spent more than 20 years on the front lines. He know things can go from calm to chaos in minutes, and being stuck in a hospital hallway for hours can make things stressful for both paramedics and their patients.

He says "They are wondering ‘What's going on, what's happening, do something, fix it.' We can't, we are powerless right now."

Hospital emergency rooms have been so backed up in 2011 there have been numerous ‘code reds,' including several on the same day, where no local ambulances are available to respond to a call.

That's what happened on Feb. 14, when no ambulances were available to respond to a call for a heart attack in Cambridge. On that day the region's paramedics spent more than 70 hours waiting outside local hospitals.

Prno says "We have to investigate that and see if the type of care we provided really had any impact on that death or if it was just a natural occurrence as such."

An ambulance had to be dispatched from Brantford to respond to the call, which is part of normal protocol when no local ambulances are available.

It took them approximately 18 minutes to reach the victim, almost double the region's target response time of ten minutes and 30 seconds.

Fire crews arrived on scene first, and Prno says, "The patient was vital signs absent when the fire department got there and was still vital signs absent when the ambulance got there. They did all the efforts that they could to try to revive that patient, and the patient did pass away."

The big question is whether a quicker ambulance response would have saved the patient's life.

But, Prno says survival rates for cardiac arrest are less than ten per cent at the best of times, and it's hard to tell whether minutes would have made a difference.

It's a scenario Stack says he's seen before, and EMS staff are tired of waiting, instead of working.

"We do monitor the calls when we are sitting there," he says. "And if we hear a serious call go out, we are handcuffed, we're tied, legally we cannot leave our patient…it can be very frustrating because you know that your skills can be put to better use elsewhere when people are more seriously injured."

Unfortunately the solution to the problem appears to be no clearer than when the situation came to light nearly a week ago.

The Waterloo Wellington Local Health Integration Network (WWLHIN) says it is working on a number of strategies to help relieve the situation.

Tony Adey, manager of public affairs at the WW LHIN says they're considering options like, "implementing more transition beds into the system, providing more health care dollars so people can get care at home. It's all of those different components working together that will help reduce those wait times."

This spring work will also begin on a traffic signal pre-emption system that will make it easier for ambulances to move quickly through the region.

That's expected to cut EMS response times by 45 to 60 seconds per call.